This library guide for MCDB 4310: Microbial Genetics and Physiology focuses on accessing historical sources relating to the four diseases that will be studied in the final unit of the class: tuberculosis, plague, influenza, and HIV. Each disease has its own page (use the tabs at the top of this guide) with descriptions and links to historical items embedded in each section. This exercise is part of a class assignment and reflection questions for these historical pieces can be found on the class worksheet.

The University of Colorado Boulder Libraries' Special Collections and Archives holds a strong collection of history of science materials. Much of this is tied to CU's history, with its strong tradition of scientific activity, but has been supplemented with major important donations and targeted acquisitions. Today, we continue to build this collection through new acquisitions to support research and instruction on campus and beyond. To find additional materials held in our Special Collections and Archives, search the following two databases:

Library Catalog Advanced Search

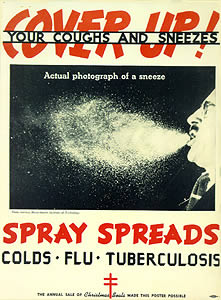

The influenza virus infects millions of people every year and evolves rapidly. Pandemics, such the infamous 1918 flu pandemic at the end of World War I, can sometimes occur when animal viruses cross over to humans. Take a look at the following sources related to descriptions of influenza, social reactions to it, and the ways that people have struggled to fight it.

Philosophical Transactions Giving Some Account of the Present Undertakings, Studies and Labours, of the Ingenious, in Many Considerable Parts of the World (1761)

The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society began in 1665 as the first journal devoted entirely to science. It is still published today.

See p. 646-647 for a letter from one physician to another describing the symptoms and treatment of an outbreak of influenza in London in 1761. Notice that this book sometimes uses an old symbol called the “long s” that looks like ſ or ʃ (it is an “s,” not an “f”).

An explanation of some archaic terms and practices to help you understand the letter.

Crassamentum is the red solid part of blood that is allowed to stand.

An 1868 description of why blistering is helpful in treating disease: “Any substance which, when applied to the skin, irritates it, and occasions a serous secretion, raising the epidermis, and inducing a vesicle. Blisters are used as counter-irritants. By exciting a disease artificially on the surface, we can often remove another which may be at the time existing internally.” From http://www.antiquusmorbus.com/English/Treatment.htm)

William Osler, The Principles and Practice of Medicine (New York, 1892).

In 1889 and 1890, a flu pandemic spread across the globe, killing about 1 million people. See William Osler’s 1892 description of influenza in his general book on medicine, found on pages 87-90.

Colorado Historical Newspaper Articles on the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (1918)

In 1918 an influenza pandemic (called “Spanish Flu” at the time) spread around the world, killing 50-100 million people (3-5% of the world’s population!). The flu reached Colorado in early October, 1918.

The U.S. Public Health Service issued an official health bulletin on influenza for local newspapers to publish in October of 1918. See the article "Uncle Sam's Advice on Flu," The Loveland Reporter, Oct. 30, 1918 (p. 4, column 5)

Next, take a look at the Golden, Colorado newspaper article "County and City Take Steps to Prevent 'Flu' Epidemic," Colorado Transcript, Oct. 10, 1918 (p. 1, column 5-6):

"School Opens After Pitched Battle with General Influ-enza," The Silver and Gold, Nov. 11, 1918 (p. 1 and 3)

"School Opens After Pitched Battle with General Influ-enza," The Silver and Gold, Nov. 11, 1918 (p. 1 and 3)

The Silver and Gold was CU Boulder's student newspaper in the early twentieth century. This issue was printed on November 11, 1918, the day CU opened after the influenza epidemic and also the day World War I ended. See the article on page 1 and its continuation on page 3.

If you are interested in viewing Helen Carpenter's diary (a freshman at CU) from the 1918 influenza epidemic, click here. (There are no questions on this document, but it might be interesting and relevant to your current experience during the COVID-19 pandemic!)

Tuberculosis (TB), formerly referred to as phthisis or consumption, has been a scourge on human populations for thousands of years. It is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and currently infects at least 1/4 of the world’s population. It was a particularly major cause of illness and death in the late 1800s and early 1900s, after the sharp rise in urbanization but before the advent of antibiotics and other treatments.

Richard Morton, Phthisiologia: or, a Treatise of Consumptions (London, 1694).

Richard Morton’s book Phthisiologia, first written in Latin in 1689, was one of the first works on tuberculosis (consumption) to be published in the English language. Notice that this book sometimes uses an old symbol called the “long s” that looks like ſ or ʃ (it is an “s,” not an “f”).

Daniel H. Whitney, The Family Physician and Guide to Health (Penn-Yan, NY, 1833).

This book details hundreds of known diseases and their possible cures. To understand how people thought about and dealt with TB in the 1800s, see the description of TB on p. 60 – 62.

The Boulder-Colorado Sanitarium (Boulder, 1920s).

The Boulder-Colorado Sanitarium (Boulder, 1920s).

The Boulder-Colorado Sanitarium was established in 1895 to treat TB, cancer and other chronic ailments, as well as to provide surgical and obstetrical care, in a pleasant “vacation” setting. Robert Frost’s daughter was treated here (this is the reason for the bronze statue of Robert Frost by Old Main). Take a look at the following pamphlet from the 1920s.

The following two images document "Heliotherapy" at the Jewish Consumptives' Relief Society Campus in the early 1900s. Photographs from: University of Denver Special Collections, Beck Archive Photograph Collection.

Plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Bubonic plague is transmitted by bites from an infected flea, which typically live on rodents. Pneumonic plague is spread between humans by coughing and sneezing. Y. pestis caused the infamous "Black Death" in the 1300s, the most deadly human pandemic the world has ever experienced. Historians define three plague pandemics in human history:

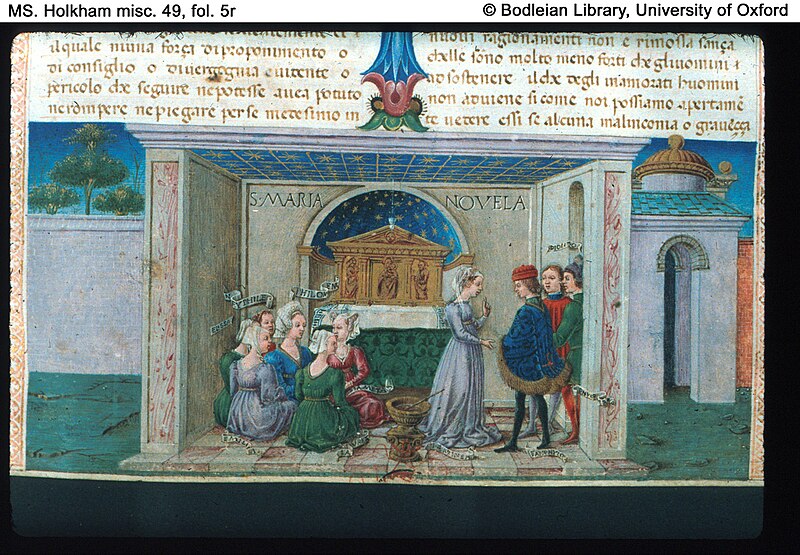

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (1353)

Boccaccio’s Decameron, written in Italy in 1353, is a fictional novel following seven young women and three young men who fled Florence to a villa outside the city during the Black Death (1348) and passed the time telling each other stories. The author lived through the pandemic in Italy and begins the book by giving graphic descriptions of the physical, psychological and social effects of bubonic plague, as well as how people of the period dealt with it. Read a few pages of the author's introduction:

London's Dreadful Visitation: Or, A Collection of All the Bills of Mortality (London, 1666).

Europe's last major plague outbreak tied to the Black Death occurred in London in 1665. Notice that this book sometimes uses an old symbol called the “long s” that looks like ſ or ʃ (it is an “s,” not an “f”). See the mortality chart for this outbreak:

"A Receipt against the Plague," Gentleman’s Magazine (London, 1743).

Plague was still a serious problem 300 years after the Black Death. As with other diseases, people attempted to create medicine to counteract the plague, as with this recipe for a potential way to fight off plague:

"Colorado Plague Summary, 2004," Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (Denver, 2004)

Plague is still present around the world and leads to a number of infections and fatalities every year. In places such as Colorado, officials test for plague. Check out the following short report on plague in Colorado from 2004:

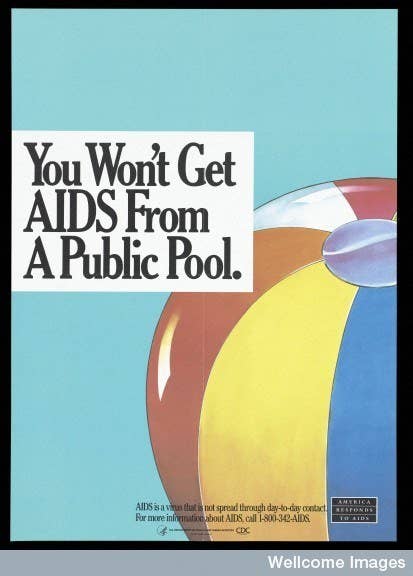

A mysterious new disease was first described in the United States in 1981. The disease, which seemed to manifest in a compromised immune system in otherwise healthy people, was first found in homosexual communities and in 1982 The New York Times and other media outlets even begin to use the term GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) to describe it. The actual causative virus, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), was identified by scientists in 1983 and the names AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) and HIV were adopted as scientists realized it could infect anyone. Because it is primarily transferred via needle swapping and sexual intercourse, social stigma has always been central to the AIDS story. In the United States, there are 1.1 million people living with HIV and nearly 40,000 new cases a year.

Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (1986)

AIDS: Information/Education Plan to Prevent and Control AIDS in the United States. Published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1987)

“AIDS: An American Tragedy,” Rolling Stone Magazine, Dec. 19, 1985