Receipt for a dike tax, Egypt, c. 160 CE

Special Collections, CU Boulder Libraries

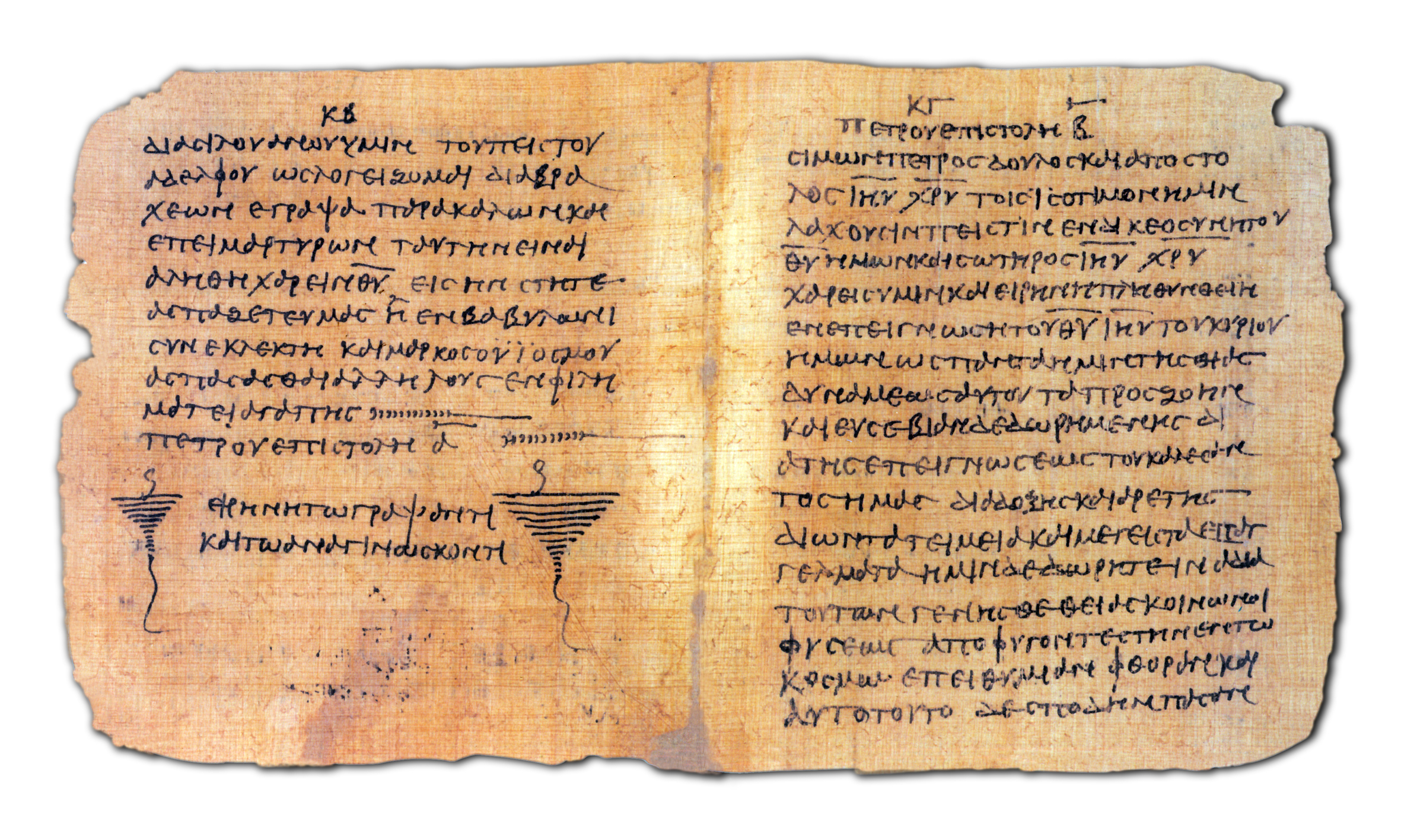

List of Books on Papyrus, Egypt, 6th Century

Special Collections, CU Boulder Libraries

Papyrus had been in use as a writing surface in Egypt from roughly 3,000 BCE.. It retained its usefulness in Greece and Rome until late antiquity, roughly coinciding with the decline of the western Roman Empire.

The Roman natural historian Pliny describes the process as one in which the inside of the triangular stalk of the plant would be cut or peeled into long strips, which were then laid in a grid pattern, dampened, pressed, dried, and polished. This process created a smooth surface, which would take ink. As seen by the piece (MS 106) held by Special Collections, which shows a 6th century CE list of books, papyrus tends to become brittle and fragment over time.

In the Early Christian period, works such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bodmer Papyri (c. 200 CE) above, were written on a similar surface. The craft of papyrus-making continues to be handed down through families (see below) living in the Nile Delta region.

SciDev.Net/ Hazem Badr

Writing in the far reaches of the Roman Empire depended upon more locally available materials. At the Romano British site of Vindolanda, thin slices of wood provided the surface for writing covering personal letters and military communication.

Letter from Octavius to Candidus concerning supplies of wheat, hides and sinews.

Tablet 343, Vindolanda, Northumberland, 1st-2nd Century, CE

British Museum

John 19:7-12, Latin Bible, c. 1100-1160, Switzerland, Ege 1,

Special Collections, CU Boulder Libraries

Over the course of the late Roman Empire, vellum - or animal skin - bound into the form of a codex - the form of our modern-day book - would become the preferred writing surface. A number of factors may have led to this change. The decline of the Roman Empire in the west and related unrest in the Mediterranean may have made the acquisition of papyrus - much of it grown in Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean - more difficult. Moreover, as a product, a leather bound codex is more durable than a scroll made of papyrus. The rise of Christianity, too, seemed to play a role.

Vellum, however, was neither economical nor easy to prepare. It has been estimated that one Bible requires roughly 200 animal skins, each requiring soaking in lime, stretching, and repeated scraping with a lunellum - a crescent-shaped knife - to prepare the surface for writing.

The ink (see demonstration, British Library) was made of oak galls, gum Arabic, and iron sulfate.

See oak gall on small branch

The durability of vellum was also conducive to illumination or decoration. Gold leaf, minerals such as malachite (green) and lapis lazuli (blue), the lapis imported into Europe from Afghanistan, and the Polish cochineal or louse (red) provided vibrant colors. Beyond medieval books highly decorative illuminated initials, many included historiated initials, or decorative initials that helped tell the story of the text that followed, such as the scene below showing Job sitting on a dung heap.

Latin Bible (Jerome, Prologue to Job - Job 5: 9). Paris, c. 1220-30, MS 317

Special Collections, CU Boulder Libraries

For more information on the technologies involved in preparing vellum or parchment, pigments, gilding, and binding, see the British Library, How to Make a Medieval Manuscript.

'Dragon Leaf,' Latin Bible, N. France, c. 1240. MS 314 (left)

Gutenberg Leaf, Latin Bible, 1455 (right)

Special Collections, CU Boulder Libraries

Displayed side-by-side, the two bible leaves shown above - Special Collections' 'Dragon Leaf' and 'Gutenberg Leaf' - demonstrate the desire by Johannes Gutenberg to produce a product that was both revolutionary in its technology and traditional in its appearance. Special Collections' 'Dragon Leaf' on the left was created on vellum, written using oak gall ink, and decorated with gold leaf and lapis in the early 13th century. Special Collections' 'Gutenberg Leaf' was letterpress printed by Johannes Gutenberg, using the moveable type made of lead, tin, antimony. The type was then set on a composing stick (see below), organized onto a galley, and printed on a press fashioned from a design with a screw-type lever similar to those of grape presses in fifteenth-century Germany.

The result was a bible very similar in its page structure and design to the earlier bibles that had graced the altars of cathedrals for centuries: double-columned, decorated with illuminated initials, and with a type-face (fraktur) very close to that of manuscript writing of northern Europe.

Gutenberg's development of moveable type revolutionized the process of communicating ideas. During the three years he was in business, he was able to print 180 bibles, roughly 180 times the speed of the copying of a bible before 1450. For more on the history of print technologies, see the British Library, Printing Landmarks.